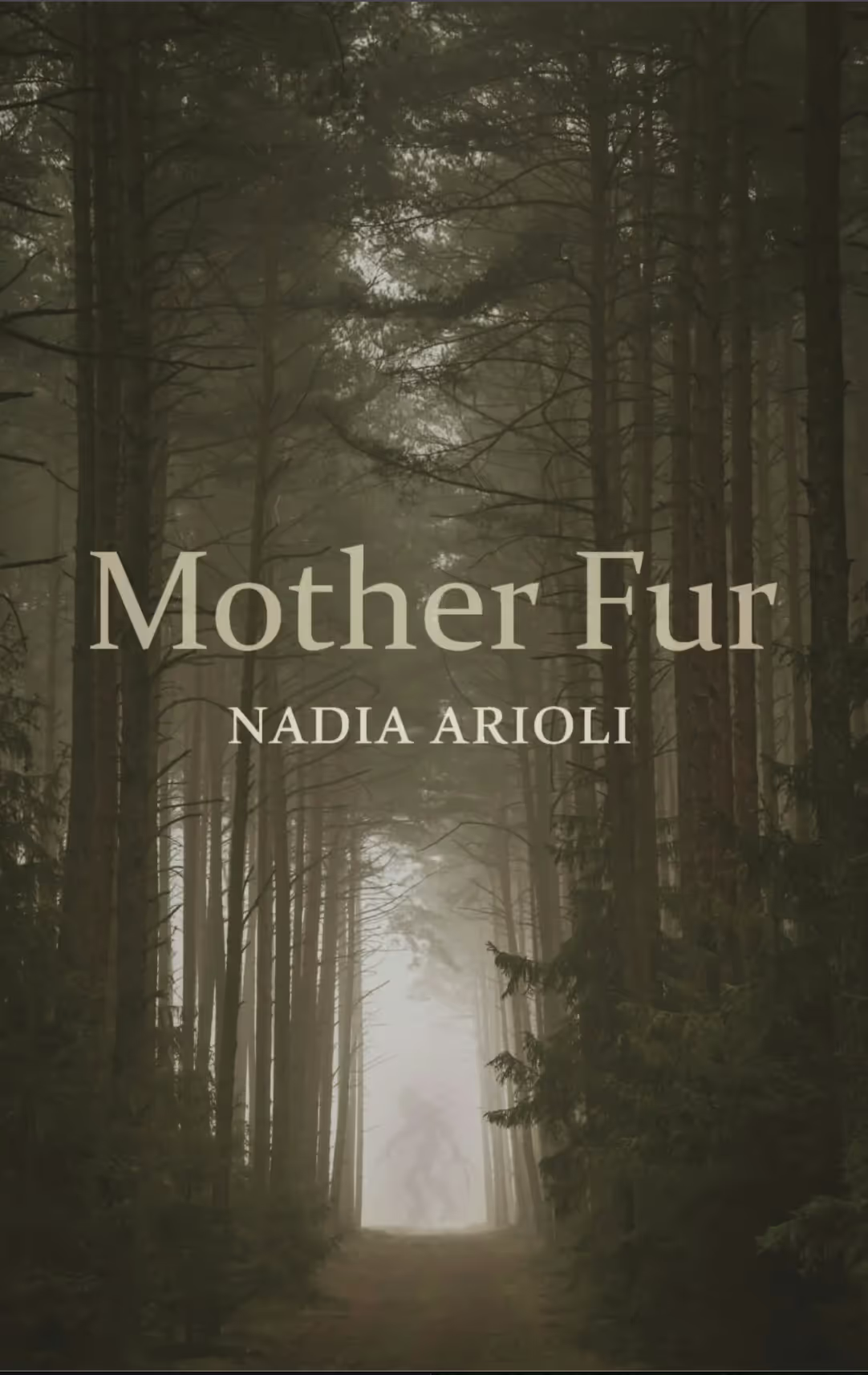

Mother Fur by Nadia Arioli

Motherhood: un-sanitized

This past summer I’ve had two friends and several more social media acquaintances go through pregnancy and have babies, meaning my Instagram feed has been flooded with beautiful photos of their journeys with baby bumps, including gorgeous Erykah Badu’s “pregnant with possibilities” shoot for Mother Tongue magazine. Were it not for books like Nadia Arioli’s Mother Fur, the world would have you believe the sanitized version of motherhood, where acknowledging the mess it creates of a woman’s body and psyche would range from inappropriate to monstrous. While social media moments are the Mary Cassatt paintings of motherhood, Mother Fur is the Nightbitch of poetry.

In the opening sequence, Painting by Mary Cassatt becomes a hinge point for the entire collection by associating the idea of creation with motherhood in the context of light, tenderness, and softness, as one would expect in a“beautiful” painting. Yet, the poem ends on a mother-and-infant museum scene with the foreshadowing line “We have always given each other unwelcome gifts.” With this one line, Arioli frames the poems in this book as an exploration of the unwanted gifts motherhood brings.

The second sequence of the book is a series of “considerations” written from the perspective of Grendel’s mother. Through the assumed lens of monstrosity, Arioli gives motherhood permission to be ugly, unhappy, exhausted, and questioning. Both parent and monster, Grendel’s mother shifts the focus away from the idea of parenting by removing the notion of fatherhood. What remains is thus less conceptual and more rooted in a surprising level of physical, palpable tether between mother and child. This sequence of poems serves to highlight how the brutality of motherhood doesn’t end at birth, it remains a consistent physical act of tearing and sharing flesh in a monster-to-monster rite of passage:

The shame and wonder of a generative force

but turned lurid by how wet it is? What could

be more wet and lurid than a mother? What could

be more wet and repulsive than a mother?

What could be more wet?

(fromGrendel’s Mother Considers Vinegar)

Throughout the collection, the language is relentless to the point of being oppressive – a way to weigh the reader down with much of what they might have never known about motherhood. With rhythm built on repetitions, wordplay, or uninterrupted stream of consciousness, these poems carry an eerie kind of music, like autopilot lullabies sung by an exhausted mother to an infant who won’t fall asleep. Grendel’s mother showcases a voice that can only grow from the depths of being immersed into the reverse out-of-body experience that follows birth not just for hours or days, but for years.

The third sequence of the book is not a sequence of poems. (Hair/Loss)is a long prose-like piece that toes the line between poem and personal essay in a narrative arc with frequent poetic and experimental detours. While the narrative arc centers around moving to a new home with a cast of supporting characters that includes husband, infant, and four cats, the overarching metaphor of hair loss as loss of identity is present and ever-shifting on every page. The voice is disarmingly honest as the speaker opens up about pregnancy loss, loss of bodily functions and autonomy during pregnancy and actual hair loss, both hers and of a loved one due to illness. However, the purpose of exposing these losses isn’t for the speaker to access grief or interrogate life after loss. This speaker is in the chaotic liminal space in between loss and grief, where one identity is still being shed while the new identity hasn’t fully formed yet. The speaker also lives in that liminal space with the cast of four cats who aptly illustrate the chaos of change by assembling themselves into feline behavioral nightmares. In the same liminal space, the speaker is“considering” family roles and generational trauma. The speaker is becoming.

Worth noting is also that (Hair/Loss) tackles an issue a large percentage of women deal with as a result of stress, aging, or medical conditions. While hair loss has been normalized in instances of cancer and in light of chemotherapy through the lens of “bravery” in the battle against the disease, outside of this diagnosis conversations on women’s hair loss is still somewhat avoided and taboo. To a large extent, this essay poem exposes motherhood as a medical condition, pitted against the family member’s own, different diagnosis, with hair loss being one of the symptoms both women experience. The line between confessional and metaphorical space thus blurred, hair loss becomes one of the characters in the narrative of the speaker’s transformation.

This final section is just as relentless in language, which makes it challenging to quote, sum-up, or explain more than to say that it explores themes of loss vs.shedding and the ways they intersect. It makes sense that it would be difficult to aptly summarize this collection because it has no resolution, no moment of sweet respite, no neat moralizing bow to tie itself in, no end in sight. In many ways, the structure and pace of the writing mirror the very experience of motherhood. The speaker acknowledges the desire (the public’s desire, but maybe also hers) for a sanitized version of the experience:

My mother, my distended belly and breasts and hair. It is not enough to bear; we must erase all evidence of doing so.

In spite of this expressed desire, or perhaps as a feminist act of defiance, Mother Fur does exactly the opposite by offering unapologetic insight into the gore that is the female body as a mother.

.avif)