The Universal Amplified

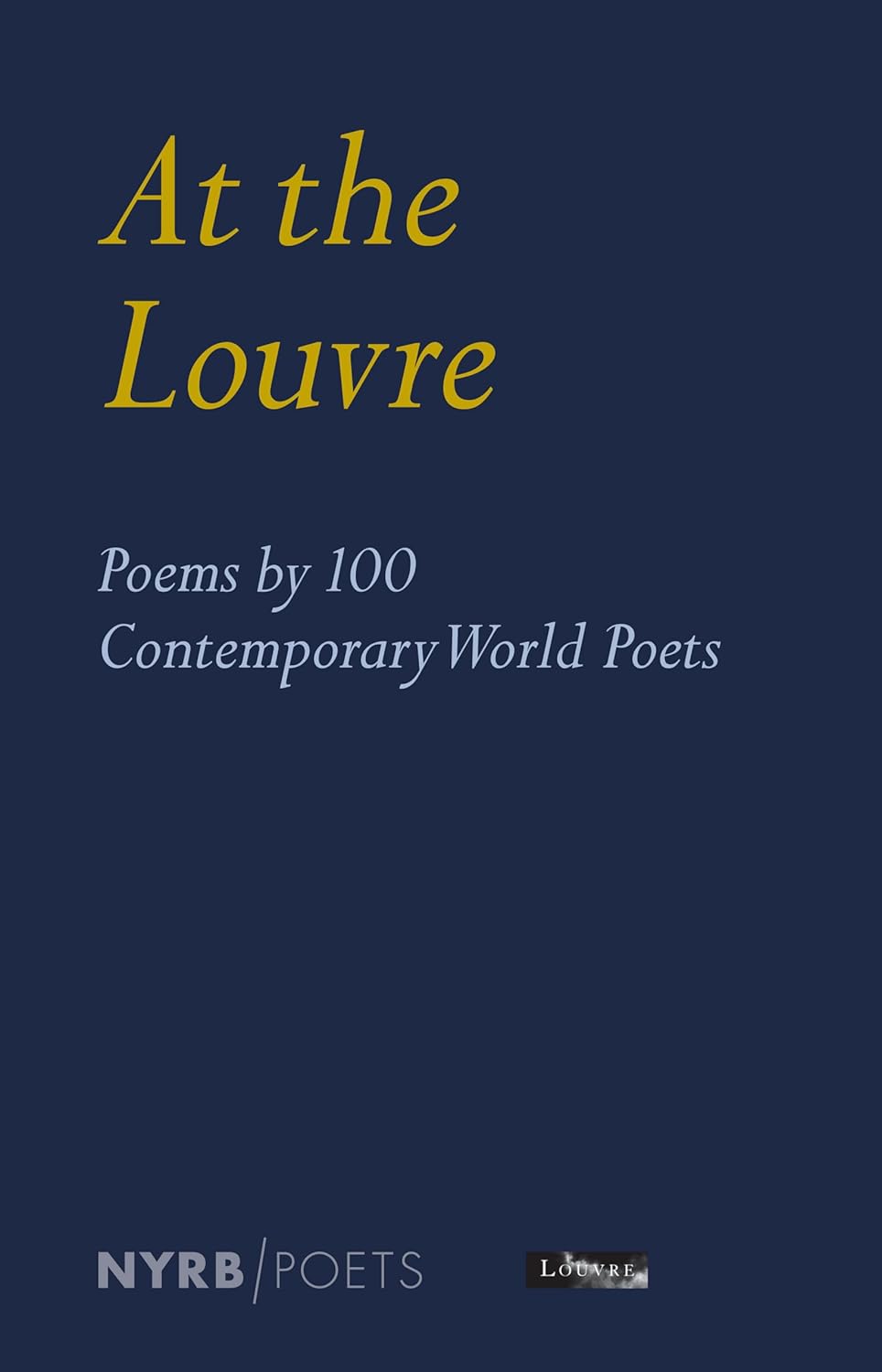

A Review of At the Louvre: Poems by 100 Contemporary World Poets, edited by Antoine Caro, Edwin Frank, and Donatien Grau

1.

Over the years, I have concluded that there are no fixed criteria as to what constitutes the continuous admiration of certain writers. Each of the critics I have read and still keep reading, for instance, I keep reading them for different but equally important reasons. I keep reading some for their seriousness, some for their enthusiasm, some for their writing style, and so on. Although these critics must boast a certain degree of these three to ensure coming back to them, certain critics have higher degree of either quality than the rest. But each of them has its own effect on the reader. For example, reading enough R. P. Blackmur’s criticism intensifies one’s love of reading poetry and reading it well because he is that enthusiastic and that serious in his critical engagements. For the assertive, freewheeling William Logan: reading him gives a young, budding critic the balls to castigate poems that are haphazardly executed and those not so deserving of the name. The British cultural polymath, Clive James, who wrote criticism with the same seriousness and enthusiasm as he did much anything else, is among these men of letters. The expectation that he features because of his writing style—propulsive, aphoristic, witty, outright gorgeous, and impressively consistent—is indeed, if not precisely, accurate. However, he features among the critics I keep rereading just as much for his enthusiastic valorization of what he calls a cosmopolitan education. He valorizes it enough across his critical writings to feel the need to correct my reading complacency. And at the moment, there is no better place to find the materials for that cosmopolitan education in poetry than by reading through the poems that make up the anthology At the Louvre: Poems by 100 Contemporary World Poets, edited by Antoine Caro, Edwin Frank, and Donatien Grau.

Although the subject of the anthology is limited to the landscape of the Louvre Museum, its copious history, and its even more copious art collections, it is anything but limited in its satisfaction of the cosmopolitan ideal: not only in its inclusion of poets both young and old from different parts of the world, but also in its accommodation of the personal contributions and cultural idiosyncrasies of these poets. In the anthology, there are poets from Nigeria, the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Palestine, Italy, Slovenia, China, Spain, Albania, Israel, Hungary, and so on, and most of them write their contribution originally in their indigenous languages. However, an English reader does not have to be a polyglot to enjoy these written words dedicated to the sheer significance of the visual arts: each poem written in a native language is here translated into English, although the anthology itself is not multilingual. (It does not print the text of the translated poems in their original languages. Rather, it indicates that so-and-so poems are translated, from what language, and by a certain translator.)

The decision to not include the original texts is hardly a bad one when the translated poems speak easily for their own strengths. A good translated poem is such because it is a good poem in the first place, at least before a worthy translator does the brain-searching task of its linguistic transference. Take for instance the poem that opens the anthology called “The Building” by the French rapper and spoken word artist Abd Al Malik translated by Alex Adriesse, who translates a considerable number of the French and Italian poems in the anthology. The poem is a series of guidance on how to navigate the vast architecture of the Louvre and admonition on how to handle its awe-inspiring spectacle on seeing it for the first time. How to take it all in, even when you are already totally awestruck: naturally, gently, silently while moving fast to take in just enough:

Stem the flux of your mind when you reach the top of the main stairs, you contemplative woman, you contemplative man.

Make it fast instead to the prow of the arch though your arms are missing though your head is missing, your heart beats;

Let the showers of light befitting silence soothe the ones who hold the apple, soothe the ones who contemplate themselves in the shield of Ares; make it fast; stem the flux of your mind; leave discord behind.

These are cautions for when the visitor is still getting through the entrance of the building. And Al Malik cautions speed because the entrance alone is enough of an arresting beauty. Even after you see the ultimate painting in Mona Lisa (“As you marvel at the eclipse of Francesco’s wife’s smile”), go through the museum enjoying its many sublime offerings, are touched and cleansed by their overwhelming sublimity, there are cautions still for how to think about those emotionally affecting artworks in the aftermath—simply as the culmination of the human imagination and our power of observation. But more importantly, as the true representation of our best and worst capabilities as human beings:

Here, then, are the steps to follow, nimble footed since the earliest empires:

All the scribes sit cross-legged meditating, roughing out our thousand and one likenesses, becoming the fire that ennobles all that’s foul within us, and a thousand and one ways of being in the world loom, swarm, and interwind, like laws engraved on a stele, the universal amplified.

So stem the flux of your mind when you reach the top of the main stairs, you contemplative woman, you contemplative man.

Reading through this poem-as-caution, one hardly feels as though reading it in translation. First, because there is no original text with which to compare it and second, because the idea behind it is a relatable, universal one: that the awe of the thing to be experienced should not hijack from us the true content of the experience itself. Throughout the anthology, French and Italian become, on Adriesse’s elegant, translating hand, languages in sacrosanct communion with their English counterpart.

A lesson in the kind of multiculturalism that does not attempt to overshadow the creative imagination behind humanism through rote, arithmetic representation, the anthology is only interested in the multiplicity of cultures not only for experiential differences and different perspectives, but also for accomplishing a sort of uniformity in these cultural varieties of the poets’ feel for the visual arts and the written words. This uniformity reveals itself in the universal morphology of human expression of her true being and various attendant conditions: the poets’ experiences of the museum and its artworks are filtered through such universal concerns like love, pain, awe, loss, etc. In “You, Ocean”, one of the early masterpieces in the anthology written by the Emirati poet Nujoom Al-Ghanem and translated brilliantly from the Arabic by the young American performance poet Forrest LaPrade, the speaker, upon getting to the museum for the first time, is nothing but cool in the bustling atmosphere of the place. But after taking in the aureate resplendence of the entrance pyramid, her dry soul instantly becomes lush, and her heart, filled with the love of the place:

Beneath my shirt the ancient

memory hides: for ages

I stood waiting, slowed by streams

of people flowing in from all sides.

Rain fell in sheets, and I

had no umbrella. But like a dry

field filled with desire,

I delighted as water rushed

down and whispered to my desert

soul: “Look! The Louvre.”

Summer storm kissing the shining

pyramid on the glass, past

stories praising a new day,

Saint Germain’s bells chiming—

like that I met and loved you.

It’s obvious Al-Ghanem had the same mind as Abd Al Malik, navigating the place gently, stemming the fluxes of her mind, unfazed by her packed environment and the less than ideal weather. She’s able to do that because her excitement is focused, contained around the singularly marvelous presence of the museum and, at the moment of her engagement with the place, nothing exists except the present:

Under your dome I dove

into an ocean of stories.

After you their souls

stayed with me.

Then my eyes looked for names

and dates, and for Liberty

Leading the People:

for an untold time great Delacroix’s

words washed over me.

Then I learned all creation

can live in one castle,

and for that I loved you.

In poetic projects like this, there are bounds to be different kinds of exaggerations like the one in the above last stanza. There are beautiful exaggerations and farcical exaggerations, but the exaggerations in At the Louvre are more beautiful than any beautiful, farcical exaggerations can be in their paradoxical weirdness. For instance, a look at a painting of a cat by the excellent Italian poet Antonella Anedda, which is the earliest instance of the ekphrastic commitment of the anthology, makes her feel the reality of death, if only momentarily and in short, quick lapses, through its stuccoed eyes:

Did she have a painful past? Was she a stray?

What does it matter. Death disappears

—each time we look, each time more quickly—

into the green-black felt of her stitched-up eyes.

Although death is not our twenty-four-hour neighbor or mate, the most efficacious beauties nonetheless tend to remind us of our ephemerality, as though that mortal reminder is the point of art. But there are other kinds of art—the beautiful beggaring the instantaneous invasiveness of fear, anxiety, irritation, and other ugly but natural states of the mind—that makes us one with what life is supposed to be about in the first place, which is living it in the present. Anedda, like other poets seeing nothing but themselves and love through the lively images of the paintings, lives in the present, giving their whole attention to the searing, emotionally transformative energy of the static worlds in whose presence they are. Their works at the Louvre—seeing, feeling, and then describing both in poetry—are worthy of anyone’s time because they are born of total immersion. There’s no other way to achieve such good poems on an experience earned in mere passing or with half a mind. So, for readers who cannot experience these physically, emotionally, and mentally exciting scenarios can at least experience the deft elan of the poets; they can experience something of the arts the poets saw and have tried their best in transmitting to us through our first medium of communication—words and metaphors and such—in the first-rate equivalence of their own emotional registrations.

2.

The anthology includes poems by some one hundred and two poets, ranging from globally renowned names like Jon Fosse, Simon Armitage, Nick Laird, and Najwan Darwish to the more obscure poets (in my experience) like the Albanian Luljeta Lleshanaku, the Malian Oxmo Puccino, the French Gaëlle Obiégly, Jacques Réda, and Blandine Rinkel; the Spanish Andrés Sánchez Robayna and the Chinese Wang Yin, among many impressive others. While the former once again prove the reasons why they are so widely revered, the latter show with convincing vitality why a considerable portion of literary reverence can be notched up to a stroke of luck. The brilliance of each of their contributions to the anthology can be gauged on the same qualitative scale, the latter most of the time edging the former by yards.

Almost every poet included that is worth the name is on her A-game, so much so that coming to Lleshanaku’s poem, titled simply “Louvre”, is like meeting one’s life partner. (I have gone on to read her books: Child of Nature, translated by Henry Israeli & Shpresa Qatipi and Negative Space, translated by Ani Gjika). She’s a glaringly distinctive poet and her contribution to the anthology includes all the impressive markers of the main. The poem is elegant and bold, the stuff of a first-rate poet in her rarest dazzle. Unlike Abd Al Malik and Al-Ghanem, Lleshanaku’s habitude to such resplendence and beauty as the one the Louvre exudes is not reserved but impatient and noticeably eager mien, and the sense of this attitude is competently annotated in her broad, ambitious figurative diction:

Waiting impatiently at the doors of Louvre

in long lines as in the Judgment Day,

separated from each other by silence

and by light whispers in different languages

that hide our common nakedness like summer clothes.

Even though Abd Al Malik’s caution and Al-Ghanem’s beautiful adherence to coolness presuppose impatience as the improper posture in the preparation for experiencing what the museum has to offer, Lleshanaku’s description is so lucid and comprehensive that she clearly represents more prototypes of museum-goers than both Abd Al Malik and Al-Ghanem combined. It’s no doubt that her visit is more productive: her third stanza is filled with the important histories of the most important visual arts in the last couple centuries, which you can now find hanging in the Louvre. Vincenzo Peruggia stole the Mona Lisa in August, 1911. There are palpable cuts on Paolo Veronese’s Wedding Feast at Cana as a result of being “stolen and transported by boat” from the San Giorgio Monastery, Venice, Italy by Napoleon’s French Revolutionary Army in 1797. Jacques-Louis David, following in Veronese’s stylistic stead, painted The Coronation of Napoleon in January, 1808, assisted by his “amateur” student, Georges Rouget, who added the finishing touches. These are communicated to us with a compressed fervor customary to poems of high seriousness. Lleshanaku’s impatient excitement is thus not an aberration but a plus: she notices, cogitates, and ultimately admires each painting she sees. Her description and conclusion are evidence enough that hers is a more wholesome experience:

That’s Louvre,

where you don’t watch but you are watched,

observed, scanned, screened through…

And the same as after screening in airports,

even though you have all your pieces back

(your belt, your watch, your shoes…)

you feel that something is still missing,

you feel that you are not the same person anymore.

These poets’ restatement of their coming and going, seeing and feeling across the Louvre, recognizing, and being recognized by the artifacts therein is the closest experience we can have as readers of the anthology behind experiencing the place at least virtually, if the physical visit is out of the question. Perhaps I glamorize a bit, but I could picture it, even if not so perfectly, how the famed pyramid of the museum and the numerous cultural and religious artifacts it contains could have a spiritual imposition on a desperate, open-minded, and grief-stricken audience from the capable, eloquent description of Yomi Ṣode in a poem called “A Pyramid of Wonder”:

Today, this glass house is my sanctuary.

A house that knows too of beauty, of loss,

praise, and breath. A house, holding our confessions,

whether day or night, and today, I am of little words.

Allow me this room to roam, to find a higher power

to ask, and keep asking,

Niké, Horse Tamers, Jesus, Venus, Lamassu,

I lost a friend today. Bring him back for me, please.

Half of the religions of the world could make a shrine out of the Louvre.

The glamorous idea put forth by Lleshanaku that the paintings watch their audience as much as the audience watches them is stretched out by Jacques Réda in “The Exhibition” and mentioned in passing by Marie de Quatrebarbes in “The Exact Weight of a Photon.” (I mean, how many times have people stared at the Mona Lisa without entertaining the sense she’s smiling right back at them?) A rationalist can say much against the easy romanticization of these artworks, animating or regarding them as sentient, but it is the imaginativeness that goes into the transposition of perspectives from the observer to the observed that makes the whole project a multicoloured rather than a monochromatic (in the sense that the poems are merely ekphrastic and historical) accomplishment. Poets like Réda regard the artworks as the ultimate cultural achievement of the human civilization or the culprits for that civilization itself, that they think of them as exactly what their makers intended: stories. And what are stories, if not living, breathing phenomenons, their usefulness and interpretation capable of changing with and anticipating us in our human boundlessness:

Look closer, and you might see a curious thing:

A vague sort of man in that enormous gathering

With a strange implement in hand (a little like a pen):

That’s me. In the eternal present, the painter had me pinned,

A humble figure of the future foreseen by the past.

I, too, have become a museum piece:

I watch my dazed human family strolling

Among what the machinery leaves among the living.

They come here as others might go mooning through a cemetery,

Visiting armless Venus, more tender than haughty,

And now that spirit has to [sic] ceased to breathe on matter,

Incapable of mastering the vagaries of the wind.

This is one of the longer achievements of the anthology. However, a critical notice of the anthology without noticing its ekphrastic aspect would have to get down to a less fancier name. The representative ekphrastic poem in the anthology is undeniably Andrés Sánchez Robayna’s “The Question.” It is a perfect rhetorical or verbal rendition of Rembrandt’s Philosopher in Meditation. Translated from Spanish by Chris Andrews, the poem reads as though the painting was done just to be versified by Robayna: his imagination is on fire and his interpretation of the painting itself is lit with the same golden light illuminating the philosopher, deep in thought. Here’s the poem in full:

Eyes linger on the eyes

of a man who wonders, in the void,

where to find order, in which world,

where, at last, he may light upon sense.

Overhead, where the stairs end?

In the room above, in the climb,

the higher ascesis, or in the embers

the woman is stirring in the fire?

Ensconced and inward, hands joined,

he sees eternity and time congeal,

the abolition of disorder and sense.

Beyond the window, the sky burns.

The absolute seriousness of this poem, especially the classic, nitpicky philosophizing sandwiched between the first and the third stanza, striking at the heart of the millennia-old curiosity about where the true meaning of life can be found—in the journey or the destination, in the outer or the inner world, in our relations with godheads or earthly acquaintances—makes the terrible contribution of Kenneth Goldsmith an utter abomination among such a clearly competitive ensemble. It’s often the case that whenever you think you have an orchard of perfect roses, there is almost always a canker nibbling against the boom of their reddish glow. Goldsmith’s poem is exactly like that sooty antagonist in the anthology: it’s a stark contrast to the anthology’s prevailing richness. A mere visual and linguistic play, his untitled piece is a minimalist arrangement of words like “JOCUND,” “ŒUVRE,” “OUVRIR,” “LOUVER,” “ROUVRE,” “L’OUVERT,” “LA GIOCO,” “LE LOUVRE,” and “DEL GIOCONDO.” They are arranged to form a pyramid, which appears to be an exercise in conceptual art rather than a considered poetic engagement with the Louvre. While it visually references the museum’s iconic pyramid and hints at the Mona Lisa (La Gioconda), its textual content offers little in the way of emotional resonance or intellectual insight. And no amount of impressionistic expository prose could conjure up a sense for its existence in the midst of these fascinating poems about artists, their artworks, and the building that houses them.

Whenever I encounter these kinds of aberration passing themselves as poetry, they remind me of Gresham’s Law, but in the opposite direction in which their kind of bad has no hope of driving out any kind of good that manage to be so through a requisite sense of the poetly responsibility. No way this kind of work has any chance of driving out such visually marvelous and sensibly ambitious poems like John Keene’s “L(’)OUVRE.” Also structured to evoke the Louvre’s pyramid, it transcends a simple architectural representation or avant-garde slush. Rather, it is a puissant and resonant exploration of the museum, particularly its complicated relationship with history and colonialism:

O

pen

your arc-

hives O muses

those bones beneath

the stones the blood the

flesh and air of wars and after-

math of conquest that powder the walls

filled with such beauty the post-colonies cry…

Keene tells it as it is: the beauty housed within the Louvre is inextricably linked to a history of conquest through blood and exploitation of nations. The “bones beneath the stones” and the “blood the flesh and air of wars” are less poetic flourishes than they are visceral reminders of the human cost embedded within the museum’s massive treasures. Hewing closely to both formal ambition and the satisfaction of narrative substance, Keene achieves the extreme opposite of what Goldsmith achieves in his smart piece.

Interminably interesting, the anthology takes the universal in the human experience and history, particularly of and with the visual arts in the Louvre, and amplifies them through the diverse voices of poets from around the world. Structured as though to advance the Jamesian clamor for the cosmopolitan education, reading across countries, languages, and cultures, the anthology keeps the poets on their toes by excluding their biographies, thereby preventing them from relying on their renown, which in assembly like this often serves as a cover for their bad attendance. The anthology will put the reader in touch with many brilliant poets and translators while understanding, in clear comparison with the good representations, the distinguishing qualities of the bad. Also, the reader is encouraged to go in search of poets that touch his soul the way the poets went in search of beauty in the Louvre. In “Gaze,” translated from the Hungarian by Ottilie Mulzet, Krisztina Tóth offers a piece of advice in engaging with the artworks in the museum that we can easily apply to our engagement with the more extensive works of the poets who so move our souls in these pages:

Let their faces be the mirror of your traveling existence,

a form replenished by the vagrant desire

to gaze back upon our brief existence here.