The Silence After the Poem

In conversation with

On eye surgeries, mythical girls, and why prose poems are like Kodak slides

KARAN

Nin, these prose poems are stunning. “Eye Operation” opens with “Eight, my unluckiest number, two zeroes, one stacked on top of the other.” So simple, so unforgettable. You write, “I was a pinned butterfly beneath the fluorescent lights.” The mother runs away in her red raincoat. The child goes under anesthesia alone. What made you return to these surgeries decades later?

NIN

The many eye surgeries I had as a child altered my understanding of reality. I have written about them many times, but I never feel I can accurately describe the experiences that remain so vivid in my mind—and shaped who I am.

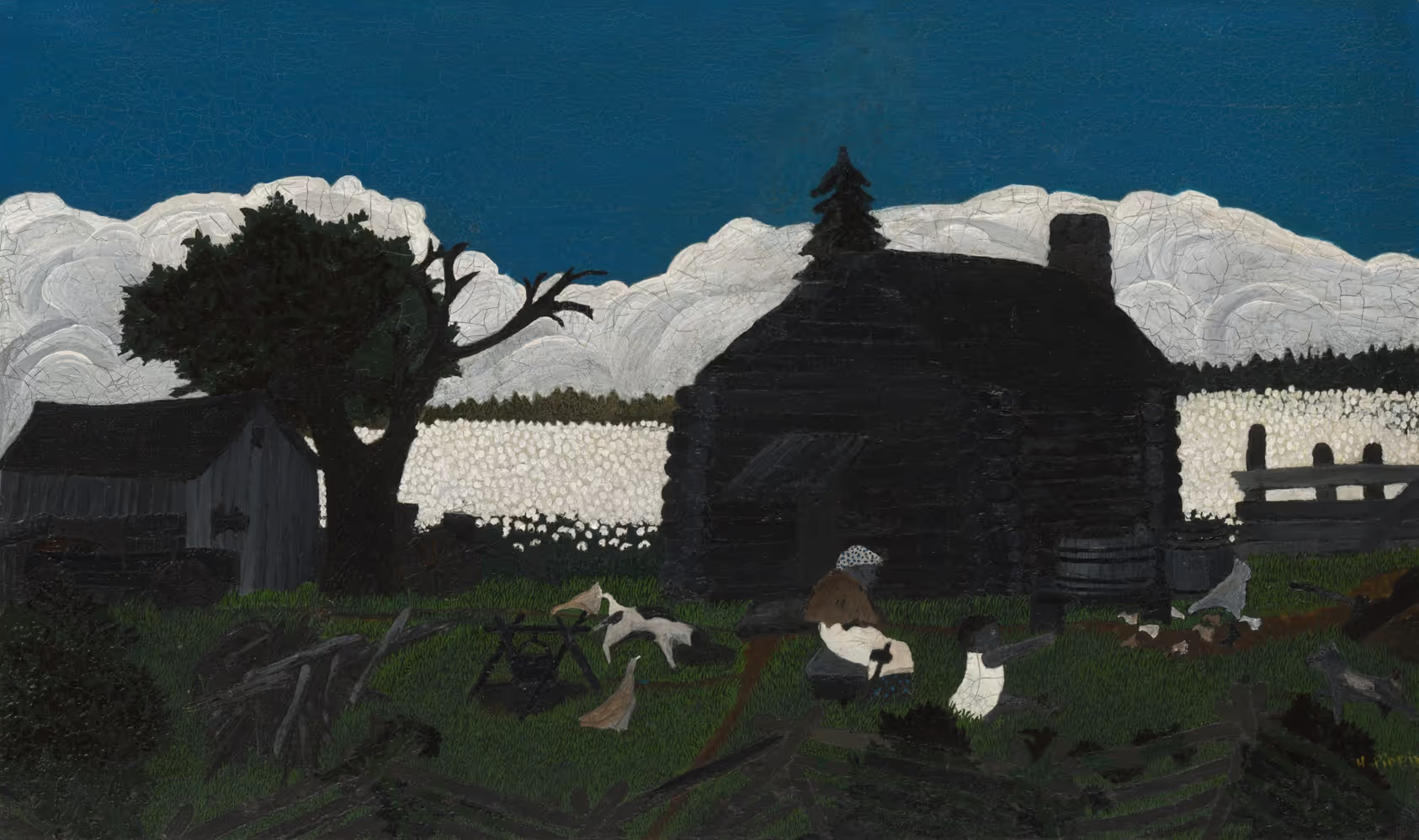

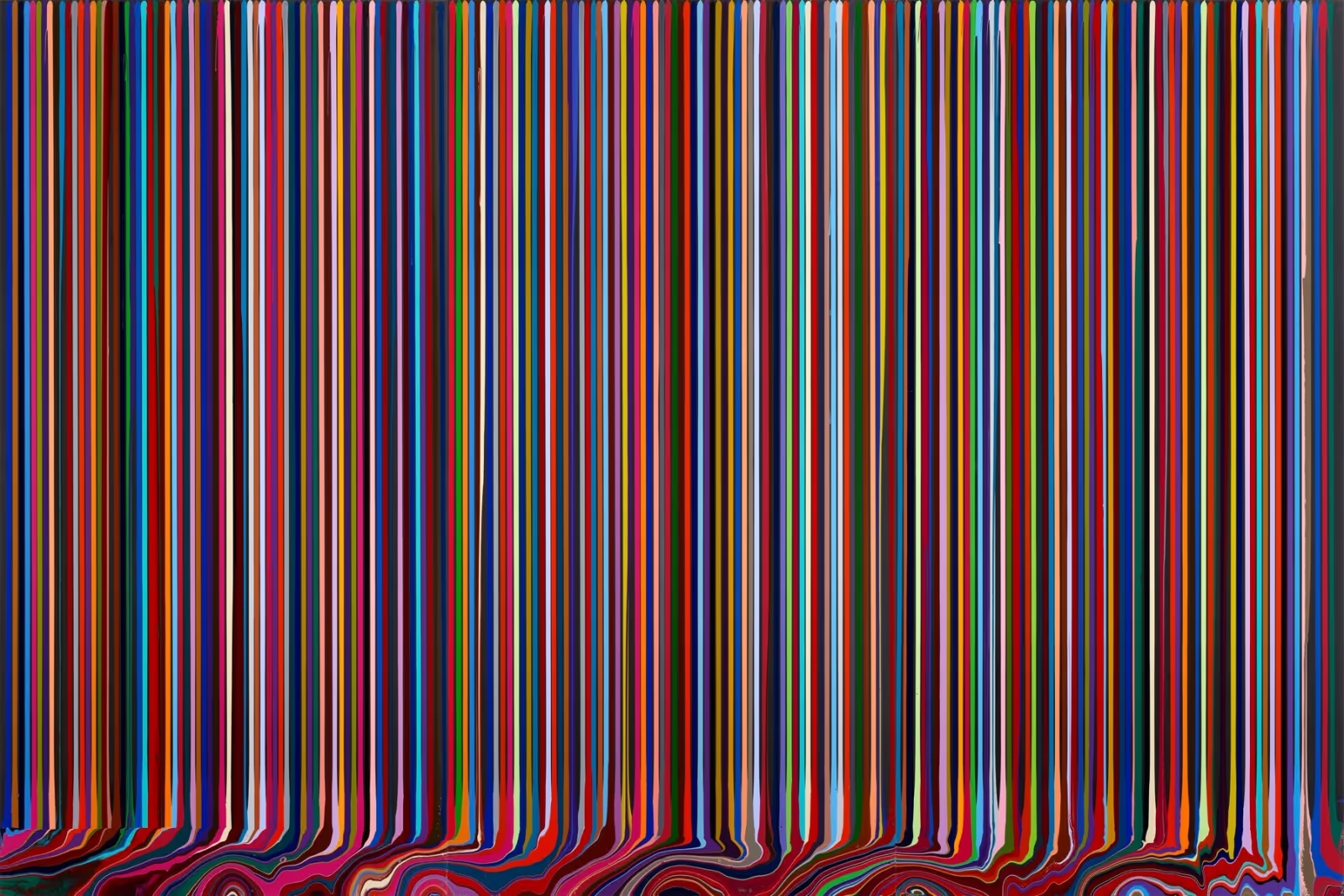

Before that particular eye surgery, the one referenced in the poem: I had nightmares that it would not go well. I reasoned that my age was the problem, the number eight was unlucky. I was very superstitious back then. Colors, numbers, names, dates were lucky or unlucky, good or evil. After my mother dropped me off at the hospital (she never stayed for surgeries), I was a nutcase, running up and down the hallways and bouncing on the hospital cot. The nurse gave me sedatives, but sedatives didn’t work on me—they simply turned my mind into a kaleidoscope, and my ears sang. When I was finally in the operating room, and the nurse placed the mask over my face, I felt my mind and body separate. I could hear the surgeon talking. I could see him like a stork bent over my body. And then, after a while, I couldn’t breathe. Afterwards, the surgeon could not wake me. When I finally opened my eyes, he was sobbing and said he thought they’d lost me. For weeks after, I was ill. My head felt like an hourglass, sand falling and falling inside it.

KARAN

“The Silence” is devastating in how it traces the making of a performed self. “Her mother always said a girl can be someone special or no one at all. The choice is hers. I will be no one, the girl knew.” Then later, as an adult, you’re “the girl in the photo on my desk, dressed in the white frothy wedding dress, who has been performing all her life.” How do you understand silence in your work? Is it survival, erasure, or something else?

NIN

I grew up on a farm, and I was always a bit ragged in appearance, so the girl in the poem is not literally me. Nor is the mother mine. I used the idea of arranging a girl as a flower designer (my mother was a talented flower arranger) as shorthand for the importance placed on a girl to become attractive. I had six eye surgeries—all cosmetic. But the quote is from my mother. As is the feeling that I have been performing. As is the feeling that I love being no one. And I love/need silence.

So this poem is both autobiographical and not.

My father used to say pretensions are all we are. I do think most people spend their lives putting on a show, to a greater or lesser degree depending on who they are. What a gift when we can stop the performance, be alone, hear no one, not even voices in our head. I think of silence as a relief and the key to survival. It’s the delicious white space in my life. The emptiness at the bottom of the page after a prose poem. A space to breathe and wonder.

I love the famous quote from Kafka:

You do not need to leave your room. Remain sitting at your table and listen. Do not even listen, simply wait, be quiet still and solitary. The world will freely offer itself to you to be unmasked, it has no choice, it will roll in ecstasy at your feet.

KARAN

The entire collection is written in prose poems—these sustained narrative blocks that accumulate incredible emotional power. In “Home Alone,” you write about erasing thoughts letter by letter until “there was nothing but blackness where words once stood.” I myself love the container of the prose block. What draws you to the prose poem?

NIN

When I look at my past, certain moments light up between long stretches of darkness, of emptiness, of forgetfulness. The lit moments have a song, a feeling, or a question I need to answer. They play and replay in my mind. Those are the moments I focus on, write from, these days.

But I want to add, the past is more than autobiography. There are the selves I never became, the girls I imagined who are still part of me, who followed the cultural myths of what a woman should be. I like to write about them, too, as I have in this series. I like to contemplate my alternate lives.

The prose poem is the form that best replicates the way my mind works. Each poem is like a Kodak slide—a little square, an image, a moment in time. The closer and longer I look, the larger an image grows. I can line my images up and click through them to create the illusion of a narrative. But there is always that darkness between the slides. And the possibility of rearranging the order at will, just as my mind does.

KARAN

“The Secret” gives us a marriage without kissing. “The kisses, like schools of fish, swam upstream without us.” I love the way you document the deprivation of intimacy. Let’s talk about process. How do you usually begin, write, and finish a poem? Where do your poems come from?

NIN

I wish I knew. Thoughts and images and dreams emerge from the mind like a herd of deer that I then try to tame. I feed them and talk to them and try to lead them into the barn or paddock, and sometimes they jump the fence. Or a hunter comes along, blam, and that’s the end. By hunter I mean, doubts or a distraction or a friend drops in for tea. Other times, they show me who they are and how they run and leap and play. The playing is what I love best. When I feel their joy.

KARAN

Animals move through this collection as figures and victims both. Baby starlings raised on Alpo. Horses treated with antipsychotics. You write, “My father debated whether animals suffer” while practicing vivisection. Meanwhile, “Birds, I thought, were small angels.” What role do animals play in your understanding of the world?

NIN

It was Descartes who practiced vivisection—a fairly common practice in the seventeenth century. My father whipped his horses but didn’t slice them open. Born in 1915, my father believed, spare the rod, spoil the child—or dog or horse. Brutality was a standard method of training. Watching my father whip his horses is one of my most terrifying memories of him—his mare, bucking and whinnying and rearing, trying desperately to escape.

Animals are such intuitive and sensitive creatures, and they understood me as a child far better than I understood them. And they were so faithful and nurturing. They knew when I was hurt or sad. Once, for example, when I was riding, the pony, slipped and fell, and miraculously, I was relatively unscathed. But until I stood up—for about five minutes, he stood over me, his head hovering over mine, his ears forward, his nose blowing and snuffling all over my face, his long whiskers tickling my skin.

KARAN

“About Suffering” connects your childhood surgeries to suicide statistics, to Nietzsche watching a horse being flogged and never speaking again, to your father flushing your baby starling down the toilet. “What saved me: animals.” The essay moves by association, leaping from your trauma to philosophy to animal suffering. Is it our suffering that connects us all?

NIN

What a beautiful question. I suppose it is! I think we are connected at the heart, which means we are connected by both our joys and our sufferings.

It is easier for me to feel that connection with animals than with people. People are animals, too, of course, but they are deceptive. They take great pains to seem other than they are.

KARAN

You have that rare skill of knowing where to end a poem. My favorite is: “death as a doorway with light leaking around the edges. The light was singing my name.” That’s such a complex image—neither fully dark nor hopeful. You’ve been open about depression throughout. How do you think about endings? Do you have any strategies? I’m hoping you’d give us a brief essay.

NIN

Oh, if only I knew how to end a poem! It’s like ending a good meal. What should you serve for dessert? Do you even need a dessert? (Often I delete my last line or lines.) If you do want a dessert, you don’t want it to be too heavy or sweet. Or too light and wifty. It depends, of course, on the meal that was served—on the whole dining experience.

I envy John Irving who never starts a novel until he knows the last sentence. Sometimes I do know the ending, but then, I get bored on the way there and never complete the poem. So, for me, as well as the reader, the last line should hold some element of surprise or discovery. Or so I hope.

KARAN

This is a question we ask all our poets, though the answers are always wildly different: there’s a theory that a poet’s work tends toward one of four major axes—poetry of the body, poetry of the mind, poetry of the heart, or poetry of the soul. Where would you place your work, if at all?

NIN

I studied religion and philosophy in college, and my first book was The Book of Orgasms. One might assume that was poetry of the body, but it was, to my mind, poetry of the soul. The orgasm was a character that couldn’t figure out why people suffer. Why couldn’t they stay with her and live as she did—in bliss and celebration?

My more recent work, including my book, Son of a Bird, a Memoir in Prose Poems, was written as a quest to figure out what happened to me as a girl—why I suffer from recurring nightmares and dreams and flashes of memory. The book covers personal territory: my farm childhood, my gay father and eccentric mother and family, and my mental breakdown. In the collection I tried to weave together the different aspects of my psyche as well as the threads of memory that hold me together and/or tear me apart.

KARAN

You’ve published many critically-acclaimed collections. What advice would you give to emerging poets?

NIN

Advice has never been my friend. When people advise me not to do something, I usually do it. Or vice versa. That’s how The Book of Orgasms began. A creative writing professor said I shouldn’t write “like that.” So, I kept writing exactly “like that.”

But I do wish I were able to follow others’ tips on how to write. Two poets who give great advice on their Substacks are Kelli Russell Agodon and Maya C. Popa.

If forced to answer the question, I would instruct someone to fall in love with the hours when writing is possible, even if they simply stare at the blank page. Then, I would instruct them to fall in love with the blank page. Then, fall in love with a few lines they scribble on the page, then, with an almost poem, then with a failed poem, then with a rejected poem—all of which are invitations to write more. And ponder.

But can I advise someone to fall in love when love happens or doesn’t according to its own whims?

KARAN

Would you offer our readers a poetry prompt—something simple, strange, or rigorous—to help them begin a new poem?

NIN

I love exaggeration. Tall tales. Magical realism. Premonitions. I love a little bit of bullshit. Or a lot of it. My father used to begin a story, “It was a day like no other day—so hot, even the birds stopped singing. And the crickets caught fire when they rubbed their legs together,” and my mother would object, “No, they didn’t.” She was very literal-minded, which would egg him on, and he’d keep going.

Or he would begin, “No one had ever seen the likes of it—the day the wind blew across the alfalfa fields, and the birds were swept up inside it along with all the clothes from the line—they went flying over the blue mountains together . . .” Or, “On September 12, 1910, I woke from a dream of my father—he was standing by my bedside, and I knew, as sure as my named is Henderson, that he would be dead by the time I opened my eyes.”

Begin a poem with something extreme—the biggest, the loneliest, the quietest, the coldest, the foggiest –whatever you choose, and follow the logic. See where it takes you.

The exercise forces you to grab the reader’s attention right away. The question is, can you keep it?

KARAN

Please recommend a piece of art (a film, a song, a painting, anything other than a poem) that’s sustained you lately or that you wish everyone could experience.

NIN

I am addicted to the song, Hallelujah. When I can’t function after reading the news or a particularly stressful day, I listen to that song. I love the Leonard Cohen version and the Pentatonix version, but there are many singers who do it justice.

KARAN

And finally, Nin, since we believe in studying masters’ masters, who are the poets who’ve most shaped your sense of what’s possible in language?

NIN

They aren’t masters, but the first language-shapers were my parents of course. They both had unforgettable styles of telling a story. My mother studied Ancient Greek with Richard Lattimore, a famous translator of Greek classics including The Iliad and The Odyssey. She raised me on the epics as well as myths and fables, and many of my early prose poems were mini-myths, often with the Orgasm as the resident goddess. In high school, I worked at a bookshop and discovered Yannis Ritsos and Gabriel Garcia Marquez—very different writers, but they both offered a kind of surreal mystical sensibility that has influenced me. In college, I discovered Henri Michaux and could not get enough of his Plume poems. I also fell in love with Charles Simic, Julio Cortazar, Louis Jenkins, Robert Bly, and other masters of the prose poem who helped me understand the hybrid form.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The song, Hallelujah, the Leonard Cohen version and the Pentatonix version.

POETRY PROMPT

Begin a poem with something extreme—the biggest, the loneliest, the quietest, the coldest, the foggiest –whatever you choose, and follow the logic. See where it takes you.

The exercise forces you to grab the reader’s attention right away. The question is, can you keep it?